In Egyptian politics, the army is king, or more precisely, kingmaker. The Muslim Brotherhood’s failure to account for this role led to its 2013 undoing, in which the military played its familiar political part, ousting Pres. Mohammed Morsi in favor of its own Fatah Abdel El Sisi, a general.

In 2015, with El Sisi’s power consolidated, military domination of Egyptian politics remains, as does the question of why the military plays such an important role. Analysts point to the institutionalization of the military into society, the massive size of its conscription and the various political roles it covers in comparison to other militaries, even other autocratic militaries.

But investigating how the Egyptian military achieved its position reveals a different set of causal factors, unsurprising amongst them, the CIA.

Scholarship from Hazem Kandil, Owen L. Sirs, as well as personal accounts — such as from former spy Miles Copeland — illustrate the extent of American connections to the continual rise of the Egyptian military regime in the early days of modern Egypt.

The CIA’s storied involvement in Egypt began in the context of 1950s Cold War meddling synonymous with the then “Third World” — a southern hemisphere loaded with potential communist dens. As early as 1952, CIA training assistance had begun in Egypt to counter communist influence in the Middle East.

CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt arrived in Cairo and began a military training program for young Egyptian officers. These young officers, as well as older members of the officer corps, formed a group of plotters known as the Free Officers Movement. The group overthrew Egyptian King Farouk, thus establishing the beginning of a 77-year-long pattern of military rule in Egypt.

[caption id=”attachment_10218" align=”aligncenter” width=”800"]

Above — Egyptian Mirage fighter jets. U.S. Marine Corps photo. At top — Pres. Fatah Abdel El Sisi. WIB photo illustration[/caption]

Maj. Gen. Muhammad Naguib was then placed into power as Egypt’s first president, as the de jure leader of a military junta named the Revolutionary Command Council. The day after the coup, the RCC invited the CIA to assist in addressing the difficulties of running post-revolutionary Egypt — the officers desired intelligence training.

Three CIA men arrived in Cairo to meet this task — James Kearn, disguised as a CBS journalist; Miles Copeland, a former Office of Strategic Services officer; and James Eichelberger, a political scientist who was the CIA’s new Chief of Station in Egypt. As many as 100 German military advisers were also brought in to assist. Some of these advisers were former Nazi SS and Gestapo.

With these arrivals, the expanding CIA presence would become a formidable supplement to the Egyptian regime’s own forces. Indeed, by some accounts, a fourth of the U.S. embassy staff in Cairo worked for the agency.

Each officer played a different role. Kearn dealt with public relations for the RCC while Eichelberger briefed the junta on reining in post-revolution contingencies. Copeland advised a Free Officer named Gamal Nasser, a prominent member of the RCC, on how to create Egypt’s new intelligence forces by consolidating the ancien regime’s political guard.

The spies cooperated with the Egyptians on several mutual security concerns, including communist dissidents, Islamist political organizations, rogue paramilitary elements, Islamist generals and potentially conspiring government ministers. Any competitors for power were now under the microscope of the American-imported intelligence expertise.

Political developments brought the CIA even closer into the fold. In 1954 Nasser exiled Naguib, cracked down on Islamist dissidents and assumed executive control of Egypt. Miles Copeland then became Nasser’s closest Western associate, and Nasser invited more CIA support.

Additional CIA training was facilitated by an Egyptian Free Officer and Nasser loyalist, Capt. Hassan al-Tohami, who supervised the new intelligence programs and the selection for CIA trainees.

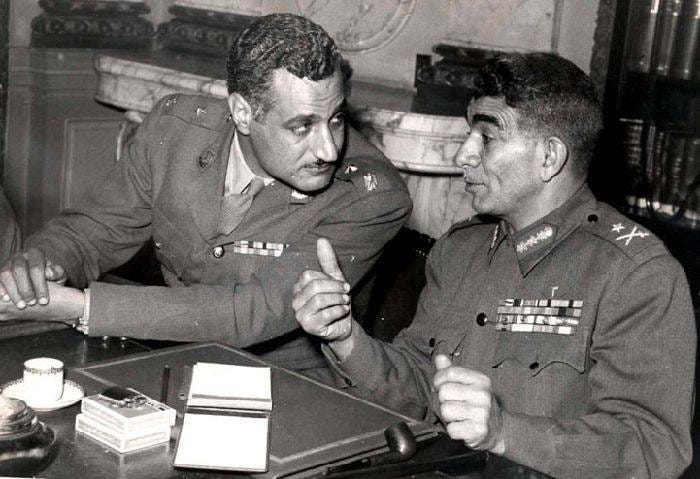

[caption id=”attachment_10216" align=”aligncenter” width=”800"]

Gamel Abdel Nasser, at left, and Muhammad Naguib. Photo via Wikimedia[/caption]

At this point in Cairo, it was hard to tell who was working for who. Al Tohami spied for both Nasser and the CIA, and the agency was also spying on both of them. An enmeshing of spy networks was inevitable. Copeland was tasked with building the General Investigations Directorate — Egypt’s intelligence branch. In line with this task, he trained police units and Nasser’s presidential body guard.

Moreover, the GID received training manuals, electronic bugs, miniature transmitters and cameras. Lastly, the CIA created a National Intelligence Estimate process for Nasser, as a structure similar to the American model of intelligence production, as to provide the Egyptian president with timely, in-depth briefs.

These years were perhaps the heyday of American spies inside Egypt. Their foundational efforts shaped the regime’s security and ascension. Indeed, according to Copeland’s book, The Game of Nations, he and other CIA operatives made Nasser the most “coup proof” leader of Africa and Asia. “We laid down a path for Nasser […] and he took it. Things might have been otherwise had he been programmed differently.”

What “otherwise” meant in Copeland’s terms was likely another regime change for Egypt. Copeland’s fondness for shadowy third world coups was uncharacteristically extreme, even for the 1950s. It was probably not a surprise to many when Copeland turned his Middle East spying experiences into a board game.

Through money, intelligence sharing and important contacts, the CIA eventually infiltrated most levels of the Egyptian government. Unfortunately for the CIA, this extension of power became an overextension, as Nasser began to distrust the CIA in the late 1950s.

The 1960s were a time of mutual consternation by Egypt and the United States owing to the burgeoning geopolitical role of Israel and shifts in American attitudes toward the latter. Although surprisingly, many intelligence cooperation patterns continued onward, in a new context of increased fear on Nasser’s part and increased CIA meddling.

While the CIA-Egyptian relationship suffered familiar Cold War ups and downs, the shared fears of communists and Islamists, coupled with the Egyptian inexperience in intelligence methods, brought the agency into the powerful role of brokering internal political events and building Egypt’s intelligence structures.

The lasting effects were a coup-proof Egypt, and the assurance of a centrist army remaining king. That is, until the brief 2011–2013 Arab Spring interruption.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق