The new buzz on antibiotics

The surface of flies is the last place you would expect to find antibiotics, yet that is exactly where a team of Australian researchers is concentrating their efforts.

Working on the theory that flies must have remarkable antimicrobial defences to survive rotting dung, meat and fruit, the team at the Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, set out to identify those antibacterial properties manifesting at different stages of a fly's development.

"Our research is a small part of a global research effort for new antibiotics, but we are looking where we believe no-one has looked before," said Ms Joanne Clarke, who presented the group's findings at the Australian Society for Microbiology Conference in Melbourne this week. The project is part of her PhD thesis.

The scientists tested four different species of fly: a house fly, a sheep blowfly, a vinegar fruit fly and the control, a Queensland fruit fly which lays its eggs in fresh fruit. These larvae do not need as much antibacterial compound because they do not come into contact with as much bacteria.

Flies go through the life stages of larvae and pupae before becoming adults. In the pupae stage, the fly is encased in a protective casing and does not feed. "We predicted they would not produce many antibiotics," said Ms Clarke.

They did not. However the larvae all showed antibacterial properties (except that of the Queensland fruit fly control).

As did all the adult fly species, including the Queensland fruit fly (which at this point requires antibacterial protection because it has contact with other flies and is mobile).

Such properties were present on the fly surface in all four species, although antibacterial properties occur in the gut as well. "You find activity in both places," said Ms Clarke.

"The reason we concentrated on the surface is because it is a simpler extraction."

The antibiotic material is extracted by drowning the flies in ethanol, then running the mixture through a filter to obtain the crude extract.

When this was placed in a solution with various bacteria including E.coli, Golden Staph, Candida (a yeast) and a common hospital pathogen, antibiotic action was observed every time.

"We are now trying to identify the specific antibacterial compounds," said Ms Clarke. Ultimately these will be chemically synthesised.

Because the compounds are not from bacteria, any genes conferring resistance to them may not be as easily transferred into pathogens. It is hoped this new form of antibiotics will have a longer effective therapeutic life.

======================

Vaccine from fly spit

Fly saliva could protect us from a dangerous disease.

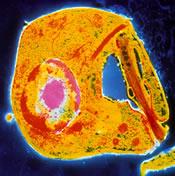

Worth spit: a new vaccine works against the fly that carries Leishmania.© SPL

Worth spit: a new vaccine works against the fly that carries Leishmania.© SPL

An injection of fly spit sounds like medieval quackery, but could be the vanguard of modern medicine. Researchers have used sand fly saliva to develop a vaccine that protects mice against leishmaniasis, a disease spread by the insect1.

This, the first potential vaccine against an insect-borne disease derived from the carrier, rather than the parasite itself, is based on chemicals that help the fly feed, preventing blood clotting and dilating blood vessels.

Leishmania, a single-celled protozoon, infects about 12 million people worldwide. Different types of leishmaniasis erode the mucus membranes of the mouth, nose and throat, or internal organs. This latter condition is often fatal.

Jose Ribeiro, of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland, focused on the skin-attacking Leishmania major, which is spread by the Middle Eastern sand fly (Phlebotomus papatasi).

The bites of uninfected sand flies seem to protect mice fromLeishmania, the group had previously found. Apparently, the same thing applies to people in South America, Africa and around the Mediterranean, where the disease is common. "Newcomers and children get sick, but they're the tip of the iceberg of those who are infected," says Ribeiro.

Ribeiro's team isolated a protein from the fly's saliva that provoked a particularly strong mouse immune response to Leishmania. They identified the gene for this protein, and injected it into mice. The mouse's cells made the protein from the DNA, triggering their immune response.

When subsequently injected with a mixture of fly saliva andLeishmania, the mice developed none of the disease symptoms. They did not eliminate the parasite, but suppressed it to one-hundredth of the level found in untreated mice. This is similar to the response of humans who are 'immunized' by fly bites, says Ribeiro.

"This is a very promising vaccine candidate," says immunologist Heidrun Moll of the University of Wurzburg, Germany. The importance of the carrier in the immune response to insect-borne disease is widely acknowledged, says Moll, but technical difficulties - such as breeding the insects and keeping them contained - has slowed progress along this avenue.

About half a dozen potential leishmaniasis vaccines have been derived from the parasite over the past decade, including one by Moll herself. Eventually, people could be immunized using a cocktail of vaccines against both fly and parasite, she says.

As well as different vaccines for different Leishmania species, we may also need vaccines based on different species of sand fly - salivary proteins vary a great deal between species, says Ribeiro. "But this is not a big deal," he assures - it takes less than two months to go from fly spit to vaccine candidate.

Researchers are also targeting the insects that carry other vaccines. One possible way to fight malaria is to develop vaccines that "do harm" to mosquitos that suck them up in human blood, says Filip Dubovsky of the Malaria Vaccine Initiative in Washington DC. As yet, there are no candidate malaria vaccines that exploit mosquito saliva.

===========

Banyan

A fly in the ointment

Myanmar’s repugnant and undemocratic constitution will haunt the process of reform

NOBODY ever expected Myanmar's democratic dawn to come up quite like thunder. But after the euphoria of by-elections on April 1st, in which the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) won 43 out of 45 seats, it did seem to be approaching fast. This week it was put back a little. On April 23rd the NLD's leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and its other successful candidates refused to take up their seats in parliament. There were echoes of the day in November 1995 when the NLD pulled out of the national convention drafting the constitution, and was left in the political wilderness. But the party played down its latest protest: not a “boycott”, it insisted, merely a “postponement”.

Indeed, the proximate cause of its withdrawal seems trivial and bureaucratic. Yet the underlying problem is fundamental to the country's hopes of democracy. That is a constitution foisted on Myanmar's people by the former junta in a farcical referendum in 2008 (a 92.48% “yes” vote on a turnout of 98.12% in a poll held just after the devastation and chaos of Cyclone Nargis).

The row was over the oath used to swear in members of parliament, requiring them to promise to “safeguard” this constitution. It seems odd that the NLD should be asked to swear this. One of the concessions made by the “civilian” government installed last year after a rigged parliamentary election in 2010 was to amend the electoral law. To persuade the NLD to join the political process, eligible parties no longer had to “safeguard” the constitution but to “respect” or “honour” it. So the inconsistency with the oath looks like an oversight. Thein Sein, the president, whose apparent commitment to reform was a chief factor in winning over Miss Suu Kyi, has been away in Japan. Perhaps, in his absence, nobody had the clout or the will to fix the matter.

It may not be quite so straightforward, however. The oath is actually incorporated as an annex to the constitution itself. And one of that charter's most objectionable features is that it can only be amended with the consent of 75% of the members of parliament. (Another, not entirely coincidental, is that 25% of the seats are reserved for the army.) The upset has drawn attention to the big unanswered questions about Myanmar's “democratisation”. Will the army ever accept amendment of the constitution? And, if not, what meaning will democracy have?

It is a document of the army, by the army, for the army. The president must have “military knowledge”. “All affairs” of the armed forces, including budgets and promotions, are beyond civilian control. A state of emergency can be declared by the president after consultation with a National Defence Security Council, dominated by the army high command and the ministry of defence. Thereafter, power is transferred to the armed forces commander-in-chief, who has the right to exercise the powers of legislature, executive and judiciary. It also provides immunity to the former junta for any misdeeds in office.

No wonder Miss Suu Kyi has campaigned on a platform of constitutional reform. Parties representing Myanmar's many ethnic minorities want other big changes, too—to reduce central-government as well as military domination. The limited devolution of power that the charter envisages falls far short of the federal structure many hope for.

No wonder, either, that there is little sign on the part of the army that it has any intention of even discussing relinquishing its power and perks. In a speech to mark Armed Forces Day on March 27th, the commander-in-chief, General Min Aung Hlaing, said the army has an obligation to defend the constitution and will continue to take part in politics. Even the reforming Thein Sein, in a speech on March 1st marking the first anniversary of the transition to civilian rule, declared: “Our country is in transition to a system of democracy with the constitution as the core.”

This was hardly a surprise from the former general. Since 2003 Myanmar's leaders have been following a seven-stage “road map to discipline-flourishing democracy”, the first four stages of which entailed drafting and embedding the constitution. But it does raise serious questions about the limits to Myanmar's reforms, and of how foreign governments should react.

Nobody can deny that Myanmar has already been transformed, hugely for the better. Many—though far from all—political prisoners have been released. The press enjoys unheard-of freedom. Miss Suu Kyi and 42 of her party are elected legislators. Liberalising economic reforms, notably of the exchange rate, have attracted a gold rush of excited foreign businesses.

To the spoilers, the victory

To reward all these positive changes, Western governments now seem to be racing each other to ease the sanctions they imposed on the junta. America and Australia have lifted some restrictions. On April 21st Japan waived nearly $4 billion in debt arrears. And on April 23rd the European Union “suspended” for one year all sanctions other than an arms embargo. Its restrictions cover: dealings with the Burmese timber, mining and gems industries; visas for members of the army and of the junta; a freeze on the assets of hundreds of individuals and firms; and the suspension of all but humanitarian aid. To ensure the measures could easily be reimposed in the event of backsliding on reform, they are suspended, not lifted. In a statement on the sanctions decision, Catherine Ashton, the EU's foreign-policy chief, said the EU was looking for progress on releasing political prisoners and ending ethnic conflicts. She did not mention the constitution at all, let alone demand explicitly that it be amended to a document embodying something closer to democracy as understood elsewhere.

Some in Myanmar see a danger in the sudden opening up of their country. A bonanza in foreign trade and investment as foreign sanctions are relaxed could end up benefiting above all the very soldiers and cronies the sanctions were intended to punish. After all, these men retain their economic interests. From this perspective all the boasts of political reform look less like a blueprint for democracy, and more like the generals' pension plan.

Correction: The above article was amended on April 28th 2012 to correct errors in the original description of the 2008 constitution. Banyan quoted from an unofficial and inaccurate translation. The article asserted that the National Defence Security Council (NDSC) could declare a state of emergency, when in fact that is the prerogative of the president after consulting the NDSC.

====================

Bill Morgan

Current and recent projects for Mr. Morgan include culturing of Borrelia burgdorferi from ticks as part of a Lyme disease survey; management of insect colonies used in Hepatitis research; and involvement in a project studying the importance of house flies as sources of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in dairy farms.

http://www.ent.msu.edu/faculty/Walker/lab/index.html

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق